Commemorating the Brandeis-based National 1970 Student Strike against the War in Vietnam

Walkouts involved more than 883 campuses and over a million students.

Boston University Strike

Boston University staff/faculty strike, 1979. Howard Zinn is standing near the front. Included in the photo are students Kateri Gasper, Lee Brotherton, Daniel Kimmel, Jim Melville, and Mark Gursky, Source: Boston Public Library. Photographer: Spencer Grant.

Register Now!

Click on the button above to register

for the Oct. 26, 2021 panel

on the National Student Strike of 1970

The event will be on Zoom,

from 7:30 P. M. - 9:00 P. M. Eastern Time.

Panel presentations and discussion will be followed by either a Q&A or breakout rooms or both.

You can view panelists' bios and pictures in the

Panelists' Bios page.

Introduction to the Event and the Panel

Gordie Fellman

Professor of Sociology

Brandeis University

1969 and 1970 were spectacular years at Brandeis. The African-American students’ takeover of Ford Hall in the winter of 1969 culminated in the creation of the Department of African and African-American Studies, the establishment of Martin Luther King, Jr. scholarships, and renewed commitments to recruit African-American students, faculty and staff.

Fast forward to May, 1970. At Yale for a rally supporting Black Panther Bobby Seale who was to go on trial in New Haven, a group of Brandeis students and two young Sociology faculty (I was not one of them) called a meeting at the Yale chapel to consider a national student strike against the war in Vietnam. In place of the few people they expected to show up, there were hundreds. It was agreed a strike would be called immediately, and Brandeis students volunteered to host it.

All but two of the entire Brandeis faculty opposed the war. In a unique meeting faculty voted to allow students who wished to work full time against the war to be graded on what they had done until the strike which began ten days before the end of classes.

Students asked Sociology professors if they could use Pearlman as the headquarters of the strike. (There was not yet a student center at Brandeis.) The answer was yes, and students, naming the National Strike Information Center, took over the building for the remainder of the semester. Pearlman was not big enough for all the anti-war activities which spilled over into rooms in Brown and Goldsmith as well.

In my recollection, about half the student body became active anti-war workers. A daily national newsletter was set up immediately, students enlisted friends from other colleges and universities (by phone; the internet was a long way off), money was raised, and organizing proceeded in Waltham as well as at Brandeis. A group of thirty or so students continued the anti-war work during the summer.

Early fall semester, a vagabond group consisting of three convicts in an experimental program, one at Brandeis and two at Northeastern University in Boston, together with two regular Brandeis undergraduates, robbed a bank in Brighton to get money for strike activities. Although he was not threatening the robbers, one of the convicts shot a police officer standing outside the bank. Patrolman Walter Schroeder died. He had been employed with the Boston Police Department for 19 years and was survived by his wife and nine children. As we commemorate the Strike, we mourn the death of Patrolman Schroeder and the grief caused his family and friends and remind ourselves that although 99% of Strike actions nationally were nonviolent, Weather Underground and other violent forces also appeared during that tumultuous time. Thus yet another aspect of the strike unfolded.

I meant to offer a fiftieth anniversary commemoration of the Strike spring of last year, but the pandemic arose suddenly, and I was not supple or quick enough to make it a Zoom event in the remaining weeks of the semester. I delayed putting a program together until this fall.

The event will be on Zoom, from 7:30-9:00 on October 26. Panel presentations and discussion will be followed by either a Q&A or breakout rooms or both. You can view panelists' bios and pictures in the Student Bios page.

Here's what lies ahead:

-

A short introduction to the panel which will be composed of me, Bob Lange, another professor active in the strike, and four students—Robbie Baer, Barry Elkin, Susan Townsend, and Jerry Zerkin— who played prominent roles in it. The panel will begin with an anecdotal history of the strike told by me and will go on to a discussion with the other five panelists of their experiences and observations.

-

A superb short article on the history of the strike with focus on Brandeis’s role. https://depts.washington.edu/moves/antiwar_may1970.shtml#strike I ASK THAT YOU READ THIS BEFORE TUNING IN TO THE PANEL.

-

Bios and picture(s) of each panelist.

-

The special issue of the student publication "The Watch" that came out late in the strike and offers its full flavor.

-

A play about the strike "When Rebellion Becomes Revolution" written and produced by the American Studies class of Professor Joyce Antler.

-

A few memos and notices from those heady days.

-

A few links to the history of the Strike Symbol.

---Gordie Fellman, recently retired Professor of Sociology

Vietnam Era

The Vietnam era was marked by serious sociopolitical dissent within the U.S. Many groups were calling for an end to the domestic and international injustices being perpetrated by the U.S. government and its agents.

Injustice

The trial of the surviving Panthers on charges of attempted murder was marked by perjury on the part of the police and FBI witnesses. All charges against the Panthers were dropped, however, none of the raiding officers ever served any time for the murders of Hampton and Clark or the wounding of the others.

NSIC

The National Strike Information Center (NSIC), the clearinghouse of pertinent information regarding the strike, was housed in Pearlman Hall at Brandeis University.

May 1970 Student Antiwar Strike by Amanda Miller

The May 1970 antiwar strikes became one of the largest coordinated sequences of disruptive protests in American history, with walkouts spreading across more than 883 campuses involving more than a million students. On April 30, 1970, President Nixon announced that American forces had invaded Cambodia in an effort to disrupt North Vietnamese supply lines. This secret widening of the Vietnam conflict drew immediate condemnation around the the world and fierce protests from antiwar activists in the United States, especially on college campuses.

May 1st, the idea for a National Student Strike was born.

18 x 25.5 inch screen print poster, which says "Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win! Strike May 4th". On May 4, 1970, students across the United States protested in response to Nixon's bombing of Cambodia. The most infamous of these protests was at Kent State University where four students were shot and killed.

"Unite," 1970, by Wally (Wayne) Zampa; poster from Michael Rossman's AOUON archive. On May 4, 1970, students across the United States protested in response to Nixon's bombing of Cambodia. The most infamous of these protests was at Kent State University where four students were shot and killed.

Photographer Joseph Karpen, 1970

Signs on the University of Washington campus raised awareness of a protest occurring in response to the Kent State shootings. Students, faculty, and staff rallied together on campus.

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, [Negative Number UW36751]

https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/uwcampus/id/35259

Protests were galvanized after the incident at Kent State University.

Panelists' Bios

Below you can read about a few students and professors that were part of the National Student Strike of 1970 and how they helped organize a strike across the U.S. and establish well defined goals and demands.

The strike was one of a series of tumultuous events during her Brandeis years which deeply influenced who she became as an adult

Robbie Baer (aka, Roberta D. Baer) was an undergraduate at Brandeis, 1967-1971. During the strike, she worked to contact other universities about what was going on and to encourage them to join the movement. For her, the strike was one of a series of tumultuous events during her Brandeis years which deeply influenced who she became as an adult, Professor of Applied Anthropology at the University of South Florida. Her current interests incorporate her longstanding concerns with social justice and community engagement: facilitating and evaluating community based COVID-19 vaccine clinics for refugees and immigrants, as well as hospital-based research to illuminate the long term effects of gunshot wounds for those who survive these injuries.

Student Activist

Robbie Baer

The activity of the Brandeis Strike committee was fascinating, exhilarating, time consuming, sobering and life changing.

Barry Elkin

Student member of the NSIC

From May, 1970: Soon after the National strike was called, Barbara Goldman and I, representing the Brandeis Strike Committee plus 2 members of the NSIC (Tony Mischel was one ) went to San Jose State to discuss what we were doing at Brandeis and to learn about what was going on at hundreds of colleges around the country. I asked then President Charles Schottland if Brandeis would pay for our tickets and he readily accepted. Of note, too was that Jesse Colin Young and the Youngbloods were in first class on the outbound jet. They brought us drinks from first class and were very interested and supportive of what we were up to). I’m not exactly sure as to exactly how we became the epicenter and information center but clearly we had our act together.

I was always aware of the goings on at the NSIC and had no other involvement other than coordinating some activities (except for fundraising the next semester to help pay the phone bill).

The activity of the Brandeis Strike committee was fascinating, exhilarating, time consuming, sobering and life changing. I watched commitment, intelligence, fear, anger, hope, adolescent sturm and drang, and the disgust with national politics from an incredible working unit of 19 and 20 year olds. And love between some of the committee members ensued. I also felt that part of my job was to listen to some of my more radical friends who wanted to be more violent and destructive and to dissuade them from those activities. It was an interesting conflict for me because emotionally I was with them and behaviorally I was not.

Watching us work together in a way that folks created their own subcommittees to address the myriad issues and needs that the strike created was mind blowing. There was so much thought, creativity, use of copy machines and computer data bases that I, as head of the committee, was intelligent enough to get out of the way so that it unfolded in a way that left us all feeling more empowered. We really felt that were doing something necessary and worthwhile.

I felt a bond with my fellow strikers and committee folk. I never had any visions, short or long term, as to how those meetings that sometimes lasted into the wee hours should eventuate. I felt more positive about what people can do with a common purpose. I also appreciated that we were quite privileged to be able to do this work without having to go to work the next day…..or have to study for finals.

After Brandeis I went straight to grad school (I wouldn’t do that now) and stayed involved with university politics for those 4 years. After grad school and before my internship at Mass Mental Health center I spent a few months collecting data in Copenhagen. While there I attended a W.H.O. conference on schizophrenia and met a psychiatrist who was practicing and teaching in Boston. After telling him “my story” he asked why I didn’t pursue politics and/or organizing. I told him that I didn’t have the patience for “the long game” and I’d rather help individuals deal with their social familial and political situations. I know that I was informed, in part, by the Brandeis Strike committee as I observed the effects of people working together for common purposes can have on themselves and others.

Gordon (Gordie) Fellman

Committed Activist Professor

1970 was my sixth year at Brandeis. A committed activist professor, I had watched and to a limited extent participated in the events surrounding the Black students’ takeover of Ford Hall in 1969. The National Student Strike against the War in Vietnam erupted a year-plus later, and I observed and took part in that from almost the start. I followed both those major phenomena with utter fascination. Two of the central questions in my sociology are 1) How do societies change? and 2) How do successful social movements work?

It occurred to me sort of reflexively to gather all the memos, newsletters, media stories, posters, etc. that I could of those two remarkably heady events. I had no plan to write about either and had no idea what to do with the cardboard cartons in my office that held the two collections.

When the university Archives was established a third of a century later in 1998, I asked Lisa Long, the first head archivist, if the materials I’d collected would be useful in the Archives. Not only did she reply with an enthusiastic Yes, she saw to it that everything in both boxes was carefully noted and organized into two files that have become among those most widely sought in the Archives by students.

“The philosophers” [are the] people—including social scientists and humanists and artists—who inquire how society works.

My time at Brandeis included being one of the four founders in the auspicious year of 1984 of what became the Peace, Conflict, and Coexistence Studies Program. For decades I taught the required introductory course eventually called Deconstructing War, Building Peace. I am now finishing a book that stems from that course and one I invented about 22 years ago called Sociology of Empowerment.

I have tried in my 55 years at Brandeis to embody the spirit and world view of Marx’s Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” I have taken the liberty of interpreting “The philosophers” as people—including social scientists and humanists and artists—who inquire how society works. This is part of what I take to be the deepest meaning of the Brandeis motto, Truth Even unto Its Innermost Parts.

Pressures in the academy are for professors to interpret more than to become change agents, but the choice is there all the same. My undergraduate education at Antioch College helped introduce me to that value and vision, and I am glad I chose it. I have tried to convey it in my teaching and am proud of countless of my students who have created one form or another of the life path of change agent.

I organize people to experience the joy of working together to make life better

Robert (Bob) Lange

Retired Physicist Professor/ Strike Activist

I got a doctorate in theoretical physics from Harvard in 1963, went to Oxford for two years as post doc, and came to Brandeis in 1965. After Martin Luther King was killed and the faculty felt it wasn’t doing enough to confront racial problems in the US, Chris Hohenemser, a fellow physics professor had the brilliant idea of the Transitional Year Program. I, with Jerry Cohen and Bill Goldsmith, got it started. It was begun as a program of the faculty, and not of the administration. That proved vital for saving it. In the first year of the program Ford Hall was taken over by Black students and many blamed TYP for it. In the following years, the administration repeatedly tried to abolish TYP but because it was a faculty program, and could be continued with a faculty vote, Paul Monsky, a committed math professor, and I were able to lead the faculty actions to keep it going. I taught math in the TYP for many years.

Shortly after coming to Brandeis I joined the anti-war activities. When Brandeis became the national leadership campus for the student strike, I turned my office over to the students and Abelson 306 became the national center for draft resistance. Several other physics professors also turned their offices over to the students.

I was promoted to associate professor in the 1970 or 71 and got the security of tenure. I started doing mathematical analysis with a friend in the psychology department related to human vision, and my research completely changed to vision at that time and continued for many years.

When sputnik, the Soviet satellite, went up, the U.S. suddenly became worried about its science education, and I joined scientists from Brandies and MIT and other institutions to try to improve elementary school science. The “hands-on” era was born. At Brandeis, I stopped my vision work when my colleague was denied tenure, and began to work closely with the Education Department, and continued teaching math and science in TYP. I became an expert at elementary school teacher training. This proved to be vital to my work as from 1988 to 1995 I led a program in science education with the Ministry of Education of Zanzibar.

I had taken a sabbatical at Roxbury Community College in Boston and met many foreign students and was concerned about their education. I was inspired by a friend who had gone to work in Nicaragua after the victory of the Sandinistas, and took a sabbatical teaching physics at the University of Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania in 1986.

I have been working in Tanzania now for 35 years, starting education and development projects there. I have retired from Brandeis, and now spend half my time in Tanzania. For the last twelve years I have been with the Maasai and sum up my work with the idea that I organize people to experience the joy of working together to make life better, and love what I am doing.

Kathy Power

Social Justice Activist

Kathy Power was part of the Brandeis contingent in New Haven when the strike was declared and returned to help establish the Strike Center on the campus, writing articles for the Strike newsletter, speaking with the press about the student demands, talking at local high schools, and traveling to Atlanta to meet with national anti-war leaders at a demonstration uniting the anti-war and civil rights movements. Frustration with the expansion of the war in the face of broad popular opposition fueled a militant politics of rage among many activists, Kathy among them. She took up what she and others thought of as a revolutionary guerrilla warfare, with disastrous consequences, including a bank robbery in which a Boston police officer was killed. Kathy spent 23 years as a fugitive, much of it on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted List. In 1993, she surrendered and served six years in prison.

She continues to work for social justice, speaking with students and community groups about her journey from war to peace and reading from her book Doing Time: Papers from Framingham Prison and from her memoir-in-progress, Surrender.

Frustration with the expansion of the war in the face of broad popular opposition fueled a militant politics of rage among many activists, Kathy among them.

Susan Townsend

Life-long activist that scheduled strike events in 1970

I lived in Waltham in a group house with someone who was at Yale with a Brandeis sociology seminar class when the strike was called. I had been moving to a class, feminist, and race analysis of things during my time at Brandeis, due to my classes, the politics around me, including the anti-war movement, and my own life experiences. When the strike was called, I started going to meetings and got involved with the local strike steering committee. It seems like there were always tasks to do, from early morning till late at night. It was the least sleep I'd ever gotten. I had to shower to let go and sleep, shower to wake up a few hours later. My main memories are of scheduling our strike events and what we did for exams. I laugh now at the shock of the administrative Brandeis staff person when she realized I was scheduling events in every bit of open space, and my shock that she thought she could. Didn't she know what was happening? I remember when Waltham high school students called to let us know they were leaving class and walking to our campus, demanding a teach-in about what was going on. I remember helping collect a list of the strike demands from various colleges and universities: US out of Cambodia and Viet Nam, Free Bobby Seale, End Capitalism Now, More Parietal Hours, etc.

I have since moved from "by any means necessary" to the means being key to goals.

I remember helping to make a documentary at a "progressive" Boston TV station about the racism of reporting: page 1 for Kent State killings, page 29 for Jackson State . . . it was never shown. I remember us deciding not to harass those who were taking finals, dancing and laughing as we decorated exam rooms with balloons and "Good luck, from your Strike Steering Committee." I remember how hard it was to separate in June, to decide what to do next with my life. And I remember the FBI descending the next Fall. These and other political times at Brandeis shaped my perspective and choices forever. I have since moved from "by any means necessary" to the means being key to goals.

Immediately after Brandeis, I was part of a Women's Health Collective in Charlottesville, VA and worked on a communist news rag for workers. I was fired from the copy center at U VA for passing out leaflets in support of the hospital workers organizing there. I participated in huge women's liberation movement meetings, went to the first openly gay dance at U VA (mostly men,) and worked at very low-paying jobs at the local newspaper, waitressing, distressing picture frames, mending horse-blankets, and working on a doughnut line at Morton's in Crozet. I went from knowing I was part of creating a socialist revolution to having to get off the assembly line to remember I could do anything!

In 1975 I moved to DC and began working at the Washington Hospital Center (now part of MedSTAR), which had just organized under SEIU, Local 722. In 1979, the RN's struck for their first contract. I worked there for 40 years, in various jobs, until I retired in October 2015. My racial politics got informed by real relationships, at work, in the union, with other lesbians in and out of political groups. I served as a shop steward, union officer, and general union listener and rabble rouser. I was able to travel with other leftist union people from DC to Honduran, El Salvador, and Nicaragua in 1986 hosted by FENASTRAS and other union people there.

Working, parenting, and now doing elder care, I have often felt exhausted, but I have stayed involved on some level throughout. I helped bring anti-racist work to my witchy organization, following in the footsteps of some amazing anti-racist activists and witches. I still do tasks of immigrant support with Takoma Park Mobilization, and get involved in some of the movements which call out police murders. Living in DC, others organize so much, so that I can be one more body in support of our climate, Black Lives Matter, women's choice, and other issues close to my heart. (Rally tomorrow for CHOICE)

Oh, and sometimes I clown! on stilts

always with the hope and intention of making a difference in changing the race and class and gender inequalities

Bob Weiser

Boy Scout to Activist

I arrived at Brandeis September 67, only a couple years removed from being a Boy Scout looking for flags to salute, and still a naive and hopeful idealist. Only a few months earlier, at my first anti-war protest, I had stood with fewer than a dozen of my 3000 HS classmates across the street from school handing out flyers for the big Peace demonstration in NYC the next day Saturday. I was jeered at loudly by my fellow Varsity Club (jocks) members. Ironically, I was unable to attend the demo because I had to work Saturday at both my day job and my night job. Fast forward to my education about class at Brandeis that Fall. During orientation, as a scholarship student, I had been part of a group of incoming freshmen greeted by Dean Driscoll. Thus, he singled me out for his wrath when I was part of a small, silent protest at the foot of the steps to the Rabb building that was being dedicated that day. The protest was in support of the United Farm Workers who were in the early stages of mounting their table grape boycott; the Rabb family owned the Stop & Shop supermarkets where scab grapes were sold. Dean Driscoll berated me for my disrespect, for 'biting the hand that feeds you'. How sad it still makes me that before I had attended my first class at Brandeis, I had received a lasting lesson on class and race inequality.

By the Fall semester of 1969, the alarming reduction in my financial aid combined with my decreased naivete, and I decided to apply for a leave of absence...from which I thought it unlikely I would return. I had never been south of DC, or west of Scranton and embarked on a thumb-fueled pilgrimage to the West Coast in February, arriving back to visit friends on campus the night Nixon announced the widening of the war. I went to New Haven for the May Day Free Bobby Seale demonstration and was part of the group that met the next day Sunday to discuss the outburst of spontaneous demonstrations in response to the escalation of the war in Southeast Asia. It was clear that this was a potentially major moment, and the hundreds of people at that meeting, from as far away as Chicago, but mostly from up and down the northeast, resolved to try to rally students nationwide for a Strike with demands that connected foreign policy with domestic policy. Thus, the goals were hammered out:

First, “that the United States government end its systematic repression of political dissidents and release all political prisoners, such as Bobby Seale and other members of the Black Panther Party.” Second, “that the United States government cease its expansion of the Vietnam war into Laos and Cambodia; that it unilaterally and immediately withdraw all forces from Southeast Asia.” And the third, “that the universities end their complicity with the U.S. war Machine by an immediate end to defense research, ROTC, counterinsurgency research, and all other such programs.”

I returned to Waltham with others at Brandeis who had agreed to form the National Strike Information Center. Part of that effort included establishing a speakers committee, and I spent the next several weeks speaking at teach-ins and rallies and school assemblies around eastern Massachusetts. At Andover High School, for example, the administration kept the students in school by agreeing to an assembly at which I debated several teachers who had served in the military. At Babson College in Wellesley, the student government presented 2 speakers, myself and the Chairman of the Boston Black Panther chapter. This was a time that extended far beyond the SDS chapters at the elite schools like Harvard and MIT and Brandeis. I spoke about the 3 demands at Dean Junior College and Pine Manor and Wheaton and Stonehill and Worcester Tech, at Andover HS and Acton-Boxboro HS, and numerous others I no longer remember. By the end of the month, I was still broke with no job.

In the 50 years since, I have worked at a wide variety of jobs...always with the hope and intention of making a difference in changing the race and class and gender inequalities that I began to understand thanks to my education, formal and informal, at Brandeis. Community organizing around housing, food, youth, and elections. Workplace organizing to form unions, or reform existing unions. My longest job ever was in a defense plant which I left after 17 years to return to Brandeis to finish my degree and become a HS teacher as I had intended in 1967. My first term back, Spring of 89, Gordie approached me saying we should organize a 20th anniversary event. I had 3 teenagers at home, a full course load, and the usual shortage of funds, so I initially said that was impossible. But, the end result was the year long, group reading, research project whose purpose was to create an appropriate commemoration of that 20th anniversary. Our students chose to have 2 class projects, not just one. They organized and led a statewide MayDay 1990 Massachusetts Student Walkout for Choice on the Boston Common and produced the May 1990 issue of The Watch that you can find on the website.

My teaching career following graduation in 90 was short-lived, but I turned my lifelong use of music as a hobby and an escape, into a central part of my life. I produced more than 1000 musical events in the Boston area in the 90s, primarily folk in the broadest sense.... traditional and contemporary...stringbands and songwriters...including blues and bluegrass and cajun etc. I've also hosted radio programs at WBRS, WADN, and WOMR-WFMR for more than 30 years. I've run and helped run political campaigns for progressive candidates, organized and supported food coops and farmers markets, rallied support for labor causes and against every war. Black Lives Matter!

In my current life on Cape Cod for the past 20 years, I host The Old Songs' Home radio show every Monday, serve as Music Director for the Harwich Cranberry Festival and CranFest in the Courtyard, and book the performers for Singing Oak House Concerts. In the larger world of folk music, I use my radio show and my relationship with other folk radio hosts around the country to try to model inclusion of all sorts. I'm proud that our trade association, Folk Alliance International, has increasingly made inclusion a principal focus in both advocacy and the business models being introduced to artists and presenters.

I realized that...I could acquire skills at law school that would enable me to contribute to progressive movements.

Gerald (Jerry) Zerkin

Activist to Attorney-at-Law

I worked in the Brandeis Strike Center in Ford Hall. More than the Strike, my world view was more the product of the information and ideas to which I was exposed during the Sanctuary, in 1967 (my freshman year), enhanced by the Ford Hall takeover, the anti-War movement more generally and the few professors who influenced my political/historical mindset. And I think the Strike deluded us into thinking that the “movement” was far more expansive in the country as a whole than it actually was. My Strike involvement, however, did help develop my need to be involved in direct political/social action.

I began as a politics major, but the department was too conservative for my taste. At the beginning of my junior year, I switched to Art History and graduated with that as my major.

My next stop was Art History graduate school at the University of Virginia. In Charlottesville, I became more connected to the realities of economic and racial injustice, not just as an academic exercise, but in the community and the realization that, for me, it was not sufficient to be an after-hours activist. I recognized that, unlike many of the political activists/organizers with whom I associated, I could acquire skills at law school that would enable me to contribute to progressive movements.

At BC Law School, I focused my clinical training on poverty law, which I continued when I returned to Virginia (Richmond). Frustrated by the limitations of that practice, I went into private practice, focusing on the representation of persons denied their civil rights and liberties, from employment discrimination to electoral redistricting, and the representation of prisoners generally and those on death row, facing the ultimate form of racial and class oppression.

In the final stages of my career, the death penalty became my primary and then sole focus. I joined the new federal public defender office in Virginia to handle, in addition to a felony case load representing mostly persons of color against the uncompromisingly harsh federal criminal justice apparatus, the defense of federal capital prosecutions, an activity I had undertaken in private practice. In time, I moved to a position in the Defender system assisting federal capital defense teams, mostly in the southeastern States. And now, post-federal retirement, I am mostly trying to undo the extreme consequences of our federal criminal justice system by helping inmates obtain the euphemistically labelled “compassionate release.”

The Watch

The Watch, a student publication, created a special edition commemorating the events of May 1970 on the 20th anniversary.

To get a closer look at the student publication click on image and then click on the zoom arrows at the top left-hand corner.

Play about the Strike

WHEN REBELLION BECOMES REVOLUTION

When Rebellion Becomes Revolution: A Play of Protest, Murder, Denial, and Atonement, was written by the students in American Studies 128, History as Theater, in Spring semester, 2012. In this course, Prof. Joyce Antler worked with students to create original documentary dramas--plays created from the historical record—on matters of social urgency. When Rebellion Becomes Revolution investigates events at Brandeis in 1970 that led to the involvement of Brandeis students in a bank robbery and the shooting death of a Boston police officer and probes the aftermath of these events. The play was performed on campus on April 2012 and again on February 2013.

Please use the following password to be able to watch the play.

Password (case sensitive): WRBR

PLAY PROGRAM, SCENES, and CHARACTERS

Learn more about the play that is linked above. Below you can find the creators of the play, the list of Acts and Scenes and the main characters in the play.

Program

"WHEN REBELLION BECOMES REVOLUTION":

A PLAY OF PROTEST, MURDER, DENIAL, AND ATONEMENT

(taken from the historical record)

WRITTEN BY

AMERICAN STUDIES 128: HISTORY-AS-THEATER

Professor Joyce Antler

Emma Avruch

Vincert Ferlisi

Deanna Heller

Paige Lurie

Herbie Rosen

Julian Seltzer

Amanda Stern

Mariah Voronoff

PRESENTED APRIL 25, 2012

INTERNATIONAL LOUNGE, BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY

Scenes

ACT ONE: THE CRIME

1.1 Orientation

1.2 Mailman High

1.3 Ford Hall

1.4 Axelrad’s Prayer

1.5 Free the Panthers

1.6 The Call to Run

1.7 Student Union

1.8 Send Money Now!

1.9 The Call Center

1.10 Strike

1.11 “They Blew It”

1.12 “Kill Us Now”

1.13 September 23

I.14 “Sick”

1.15 Police Headquarters

1.16 Who is Kathy Power?

1.17 Who is Susan Saxe?

1.18 Life Goes On

1.19 The Schroeders

1.20 A Brandeis Offer

1.21 The Board of Trustees

1.22 Faculty Demand an Inquest

1.23 Dean Diamondopoulos

1.24 Soul-Searching

1.25 Fear in Academia

1.26 A “Soldier”

ACT TWO: TRIAL

2.1 Teach-In

2.2 Fugitives

2.3 Arrested

2.4 Free Susan Saxe!

2.5 “I’m Not A Monster”

2.6 “Susan” Gertner

2.7 Howard Zinn Protests

2.8 Fleisher Takes the Stand

2.9 The Defense Rests

2.10 Verdict

2.11 The Plea

2.12 A New Revolution

ACT THREE: FORGIVENESS

3.1 The Long Search

3.2 Surrender

3.3 The Schroeders Reflect

3.4 Doing Time

3.5 Parole Hearing

3.5 Prayer

3.7 Release

3.8 Gunman

3.9 Reunion

There will be a 5-minute intermission after Act One.

Main Characters

MAIN CHARACTERS

MORRIS ABRAM served as the second president of Brandeis from 1968-1970. A well respected lawyer, Abrams was a strong civil rights advocate.

RABBI AL AXELRAD came to Brandeis in 1965, where he served as Chaplain and Hillel Director for 36 years. He is currently Chair and Adjunct Professor of Religion at the Center for Spiritual Life of Emerson College.

STANLEY BOND was a former convict involved in the STEP program at Brandeis. After organizing the robbery of State Street Bank, Bond served a short time behind bars, dying before he could go to trial.

JERRY COHEN, a professor of American Studies at Brandeis, was one of the founders of the Transitional Year Program. He celebrated his 50th year teaching at Brandeis last year.

PETER DIAMONDOPOULOUS was the Dean of the Faculty in 1970. He went on to become the President of Adelphi University.

BARRY ELKIN served as the Brandeis Student Union President in 1970, graduating in 1971. He is a psychologist in Lexington, Mass.

GORDIE FELLMAN has taught in Brandeis’ Sociology Department since 1964. He directs the program in Peace, Conflict, and Coexistence Studies.

MICHAEL FLEISHER was a Brandeis student and anti-war activist who was a member of SAXE and POWER’s anti-war group. He has been a social worker in Chicago for many years.

NEIL FRIEDMAN was a leftist professor of Sociology and Brandeis graduate (class of ’61) who had a strong influence over Brandeis radical students.

JOHN GAFFNEY was the Assistant District Attorney in charge of the Susan Saxe case.

NANCY GERTNER was a criminal defense attorney for over twenty years; she became a US District Court judge in 1994, known for bold decisions regarding race and civil rights. Retiring in 2011, she currently teaches at Harvard Law School.

MAIN CHARACTERS CONTINUED

WILLIAM GILDAY, a member of the group who robbed State Street Bank, remained in prison until his death at age 82.

MARVIN MEYERS taught in the History Department at Brandeis from 1963-1985.

KATHY POWER would have graduated with Brandeis’ class of 1971. Instead, she spent her last year on the run after robbing a bank in Brighton. She now lives in the Boston area.

SUSAN SAXE is a Brandeis alumna, class of 1970. She currently lives with her partner and children in Philadelphia, where she is the chief operating office for ALEPH, the Alliance for Jewish Renewal.

CHARLES SCHOTTLAND, dean of Heller School for Advanced Studies in Social Welfare, served as president of Brandeis from 1970-1972 after the resignation of Morris B. Abram.

CLAIRE SCHROEDER, daughter of Walter Schroeder, became Waltham's first female police officer in 1978, retiring as a sergeant in 1995.

MARIE SCHROEDER, widow of Walter Schroeder, moved her family to Waltham where she was a traffic supervisor for more than 15 years.

JOHN SPIEGEL was a nationally renowned social psychiatrist and a professor at Brandeis University. He headed the Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence.

ROBERT VALERI testified against the group involved in the robbery and served a short time in prison.

HOWARD ZINN was an American historian, social activist, and playwright. Among his books is A People’s History of the United States.

Note

PROGRAM NOTE:

Many thanks to the Brandeis University Archives and to Nancy Gertner, for generously sharing her materials, and to Jerry Cohen, Barry Elkin, Gordie Fellman, Nancy Gertner, Kathy Power, Bob Schwartz, and David Squire, for sharing their memories. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Melanie Zoltan, Angie Simeone, and Nathan Koskella of the American Studies office, and of Maggie McNeely of the Brandeis Archives.

HOOT REVIEW OF THE PLAY

Published: February 13, 2013

In Hebrew it’s called emet. In English, however, perhaps most of us know it better as truth.

At Brandeis, we encounter this word daily. It’s thrown around in conversations and pursued in campus clubs. Other times, students have protested for it. Mostly, at Brandeis, we search for truth as a way to realize social justice—in all of its forms—through the education we have created for ourselves. Truth, after all, is engraved in the very motto of our university.

The rich history of students seeking truth at Brandeis was articulately retold at “When Rebellion Becomes Revolution: A Play of Protest, Murder, Denial and Atonement” that was well performed during this past weekend in Schwartz Hall. Presented with sponsorship by the Free Play Cooperative, the American studies program, and with support from ’Deis Impact 2013, the play was entirely student written and produced. Originally written in the spring of 2012 by the students of Professor Joyce Antler’s History-as-Theater class, “When Rebellion Becomes Revolution,” it paints a historical landscape of Brandeis during the anti-war movement—specifically those against the Vietnam War starting in the late 1950s.

The play utilizes a cast of 14 actors to depict more than 50 historical figures. The main narrative, however, is that of two radical Brandeis students, Susan Saxe and Kathy Power, and their involvement within and outside of campus during this tumultuous period of American history. The two are also among eight women to have ever made the FBI’s most wanted list. Most famously, and in which the play centers heavily on, is the robbery of a Brighton Bank that resulted in the death of Boston Police Walter Schroeder by the duo and their accomplices. In the process, the play outlines an informative tale of Brandeis students engaging in their individual vision of social justice. This includes turning Pearlman Hall into a major strike center and the taking over of Ford Hall by the Brandeis Afro-American society, just to name a few.

With such an endearing legacy of social involvement at Brandeis, the play makes a valiant effort of not only getting the story right, but also presenting an extensively long history within the standard length of a play. In drafting the script, Amanda Stern ’15 and Julian Seltzer ’15—two of the play’s original co-authors—dug deep into the archival records of Brandeis to collect newspapers, flyers, interviews and a myriad of other primary documents to accurately capture the history and social climate in which “When Rebellion Becomes Revolution” takes place. Their dedication to the research, as well as being co-directors and producers, was displayed in how well the play was able to vividly recount an entire era.

Building off the hard work of Stern and Seltzer, the second part of the equation to what made “When Rebellion Becomes Revolution” so stunning and successful was the 14-member student ensemble cast. Ranging from those who have never acted before coming Brandeis to seasoned thespians, each cast member truly committed to bringing his or her historical figure alive. The amount of work they invested into this production was highly evident. This was clear from the eloquent performance by the entire cast. All 14 members of the cast were terrific in the way they treated each of the characters they played as separate individuals with unique idiosyncrasy, particularly of the performances from Steve Kline ’14, Jen Largaespada ’16 and Phil Skokos ’15. Kline, having played a total of six different characters, was a true chameleon in the way he was able to shift from tossing around the murmuring Boston accent of Police Commissioner Edmund McNamara to embodying the stoic intensity of former Brandeis President Morris Abrams, and even to the calculating coolness of Prosecutor Gaffney.

Brian Dorfman ’16 gave a very believable performance as the younger, though still characteristically laid back, Gordie Fellman. The two reporters, Julia Doucet ’16 and Gabe Guerra ’14, were great in their ability to help narrate and transition between the scenes.

Two standouts, however, were Stern as Susan Saxe and Barbara Spidle ’16 as Claire Schroeder. Being a part of eight total women to make the FBI’s most wanted list, playing Susan Saxe meant depicting a fearless, strong, intelligent woman, unyielding to her own ambitions and goals. Stern, who on top of helping produce and direct the show, played Saxe with all of these qualities. Most impressive was the passion and belief in the delivery of her ending monologue to the first half of the play, in which she vehemently voiced protest against America’s actions during the war, crying: “America, your children hate you!”

Spidle, as Claire Schroeder, brought great contrast to Stern’s performance. Depicting another strong woman figure as the daughter of Walter Schroeder, Spidle skillfully instilled a fragility and vulnerability to her character. She was able to show Schroeder’s struggle between choosing to forgive Saxe and Kathy Powers (Barbara Rugg ’15) for the murder of her father, or remaining angry with them. Spidle’s performance as Claire Schroeder is also noteworthy in that it brings a refreshingly surprising message to the play, one about finding forgiveness as a way to peace. This was clear in Spidle’s performance as Claire as well as from Stern and Rugg who showed the journey of their characters realizing their actions, atoning for them in their own way, and ultimately forgiving themselves.

There was very minimal prop use throughout the play and actors kept their costumes simple. Indeed, it was not the vintage vest worn by David Friedman ’15, nor the fringed poncho donned by Jess Plante ’16 that captured the time period. Instead, it was the ability of the cast to give a voice to the story of Susan Saxe and Kathy Powers that made the production truly stunning.

“When Rebellion Becomes Revolution” lives up to the legacy of Brandeis students seeking to realize their own vision of social justice through doing what they believed to be right. In the end, “When Rebellion Becomes Revolution” was powerful in the history it revealed and each cast member’s passion resonated in the core themes presented.

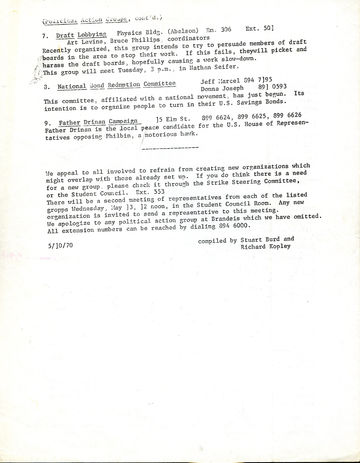

Below are some of the memos and notices from the strike that are now a part of Brandeis University archives. To enlarge, click on an image and then click on zoom arrows at the top left-hand corner.

Strike Memos and Notices

Criticism of American society has continued . . . particularly on two grounds: first, that it has excluded a significant minority from its prosperity, and second, that affluence alone is empty and potentially dangerous without humanitarian, aesthetic, or expressive fulfillment.

Oil on canvas painting "The Uprising" (L'Emeute) by Honoré Daumier, 1848 or later.

If student activists of the 1990s can find that their demonstrations and actions are effective in molding social change, then the constructive force of activism on American society may again approach the productive level of the student movement of the 1970s.

Articles on the Symbol of Resistance

Below are three articles on the history of the raised/clenched fist which can be seen in pictures of students from the strike as well as on posters promoting the strike.

Origins of the Clenched Fist

A Brief History of the Raised Fist

National Geographic - The History of the Raised Fist

"STRIKE,", reproduced in Unite Against the War, folio of posters from 1970.